The History of Dry Ridge

The Story of a Black Family and Post-Civil War Community in Clark County, Kentucky

Jane Wilson House at Dry Ridge

Introduction

Post-Civil War Clark County saw the development of several black communities that are still well known today. In Winchester, Poynterville first appeared on maps in 1877. In the western end of the county, Lisletown and Hootentown are still familiar place names even though the last black families moved away years ago. One community that has escaped wide recognition locally was called “Dry Ridge.” It was located near Schollsville, on a ridge south of Bethlehem Christian Church. This is the story of Dry Ridge and the family that settled there.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

Ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865 abolished slavery in the United States. Freedmen, however, would experience difficult times in post-Civil War Kentucky. For blacks the issues seemed simple: “Give us the rights of other American citizens, let us enjoy those freedoms without hindrance and allow us to go on with our lives as we too seek a better future.” Not a single one of those actions would occur without dispute or restriction, as “white Kentuckians refused to replace the scheme of dominant and subordinate status with a system of equality.”

Many freedmen were put off the land with only the clothes on their backs. Large numbers fled to the cities or left the state. Of those that stayed, the majority of men worked for wages as farm laborers, the women in domestic service, and most families lived in extreme poverty. Those with a skilled trade fared better than others.

There were widespread complaints that blacks were not receiving anywhere near the same wages as whites were paid for the same work. The Freedmen’s Bureau tried to assist by mediating contracts, but only nine such contracts appear in the records for Clark County.

Another problem freedmen faced was having their children bound out as apprentices, girls “to be taught the art of housekeeping” and boys “to be taught the art of farming.” According to Kentucky historian, Thomas D. Clark, this “created a new form of involuntary servitude.”

Possibly the greatest menace in the decades following the war was the constant threat of violence. There were numerous reports of atrocities—beatings, murders and destruction of property—by groups of “Regulators” as well as the Ku Klux Klan. Horrific crimes were reported in the nearby counties of Bath, Bourbon, Harrison, Scott, Fayette, Madison and Estill.

Within the first two decades of Dry Ridge occupancy, Clark County had two lynchings that were reported—Ben Johnson in 1880 and Robert Haggard in 1895, both of color.

Although no incidents are recorded for Dry Ridge—only a handful of newspapers survive from that period—it would be surprising if blacks there completely escaped systematic harassment. And the fear of violence itself is a form of terrorism.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

A few fortunate individuals who managed to earn and save enough money acquired property in one of the African American communities that sprang up in Clark County after the Civil War.

One of these communities was Dry Ridge, located at the northern end of Indian Old Fields in Clark County, near Schollsville. The community was the legacy of Moses Robinson, whose will directed his executor to acquire farms for each of his children: Jane Wilson, Andy Robinson and Permelia Alexander. Jane, Andy and Permelia’s son Moses settled there. Though life must have been hard on Dry Ridge, the land Moses left certainly helped his children and their descendants to a better future than they might have had without it.

Dry Ridge is located along a north-south ridge beginning about a half mile south of Bethlehem Church. The name may relate to the absence of springs and perennial streams on the ridge. Although occupied by blacks for nearly 150 years, the name “Dry Ridge” makes only a few scattered appearances in county records.

Moses Robinson

Moses Robinson was one of the most notable early African-American residents of Clark County. Despite the stark racial discrimination of the Antebellum Period, he managed to provide a remarkable degree of support for his family. His net worth at the time of his death may have exceeded that of any black man in the county prior to Emancipation. As impressive as this was, the focus of his labor was yet more significant. He used his earnings to win freedom for his family before Emancipation and, after his passing, to acquire land for his children.

Moses was born into slavery in about 1792 in Kentucky. While his early history is uncertain, in January 1832 his owner, John Robinson, went before the Fayette County Court and testified, “In Consideration of the Services of my black man Moses have this day by these presents Set free & emancipated the said boy.” Despite the condescending language of the times—referring to a 40-year-old man as “boy”—John Robinson must have held Moses in high regard.

Though we can find no record of a marriage, Moses’ wife was named Milly. She was free by 1850. We cannot say if this was the work of Moses, as the record of her emancipation has not been found. At the time the 1850 census was recorded she was living with her daughter Emily. It is not known if her separation from Moses was temporary or permanent. Milly is the presumed mother of Moses’ other three children—Sarah Jane, Andy and Permelia.

Moses moved from Fayette to Clark County where he was recorded in the 1840, ’50 and ’60 censuses. He is not listed on any of the Clark County tax rolls in the 1830s, so he may have removed to Clark in about 1840. That year the census recorded 145 free blacks in the county including children out of a total population of 10,802. Enslaved blacks (3,902) greatly outnumbered free blacks.

Free blacks did not enjoy the same privileges accorded to whites. Any perceived transgressions were severely punished. There was no prison for free blacks, and they were for the most part subject to the “slave laws.” These called for the death sentence for a lengthy list of crimes, including manslaughter, arson, rape, and destruction of public property. For minor transgressions freemen were subjected to corporal punishment—public whipping—and fines. Moses must have avoided serious trouble as a free man. We don’t find his name listed in any of the civil or criminal proceedings during his time in Clark County.

In the 1850 census Moses was listed as a laborer, still living alone. In 1860 he gave his occupation as shoemaker and reported a personal estate of $3,800. This equaled or exceeded the worth of many whites living in his area—a rare accomplishment and an indication of Moses’ financial ability and thrift. His 22-year-old son Andy, a day laborer, was living with him.

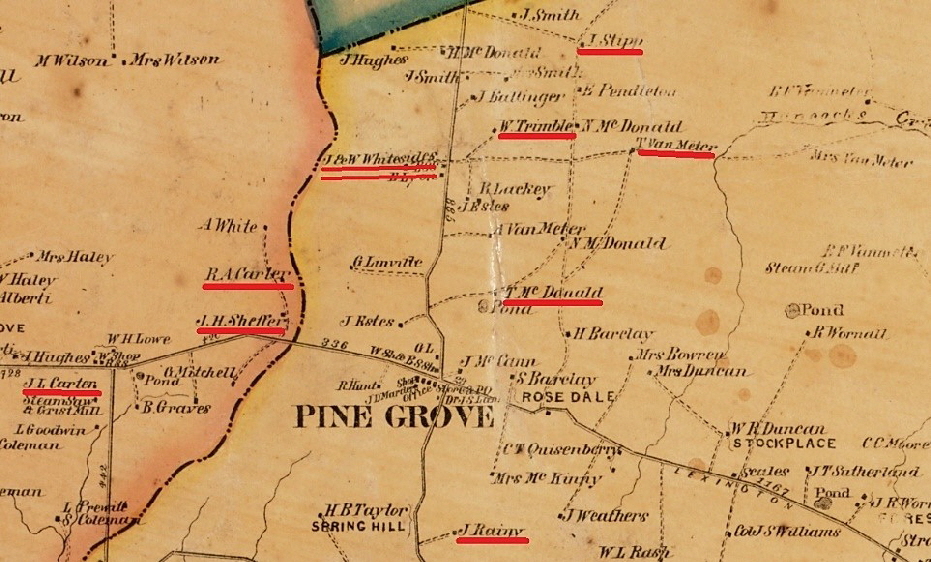

Moses Robinson’s 1860 Residence in Northwest Clark County Moses lived near John & William Whitesides (double underline). Moses held notes on the eight underlined individuals.

From the names of his close neighbors, as listed in the 1850 and 1860 censuses, we know Moses resided in northwest Clark County near the intersection of Clintonville and Van Meter roads.

Moses used his earnings to purchase his daughter Emily and two of her children, Sarah and Dickerson, owned by Thomas Ellis of Fayette County. He then went to court and obtained a certificate of emancipation for each in 1841.

Thomas Ellis’ will called for Moses’ other three children—Sarah Jane, Andrew and Permelia—and their offspring to be freed at the death of his wife (she died in 1858).

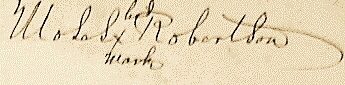

Moses died in 1861. He left a will, written in 1849, devising all his estate to his children whom he named—“Emily, the wife of Francis Mitchal; Sarah Jane, the wife of Charles [Wilson]; Andrew; Parmelia, the wife of Gustus Alexander.” He signed the will with his mark. The clerk who copied the will misspelled his name as “Robertson.”

Moses’ “signature” on his will.

The material goods Moses left behind—a horse and buggy, a saddle, shoemaker’s tools, two shotguns and a pistol, silver watch, a few pieces of furniture, utensils and other odds and ends—are not suggestive of a wealthy man. When sold, the whole lot amounted to only $86.10.

John Whitesides conducted the sale Moses’ personal estate at Moses’ residence in May 1861. All of his children attended the sale. Permelia purchased a stone jar and crock (65 cents), Emily a saw and slate (10 cents), and Jane coffee and sugar (5 cents). Andy, who was listed with a personal estate of $300 in 1860, purchased a good portion of his father’s possessions, including his shoemaker’s tools ($2.35), silver watch ($1.80), two bibles and a hymn book (5 cents), a safe with its contents (50 cents), two axes and a grindstone ($1.05), plus a few other odds and ends. Andy was also high bidder on the most expensive item in the sale: Moses’ buggy and harness for which Andy paid $39. (He already owned two horses.) A Robert Robinson bought Moses’ horse for $20; it is not known if he was a kinsman, or even if he was black.

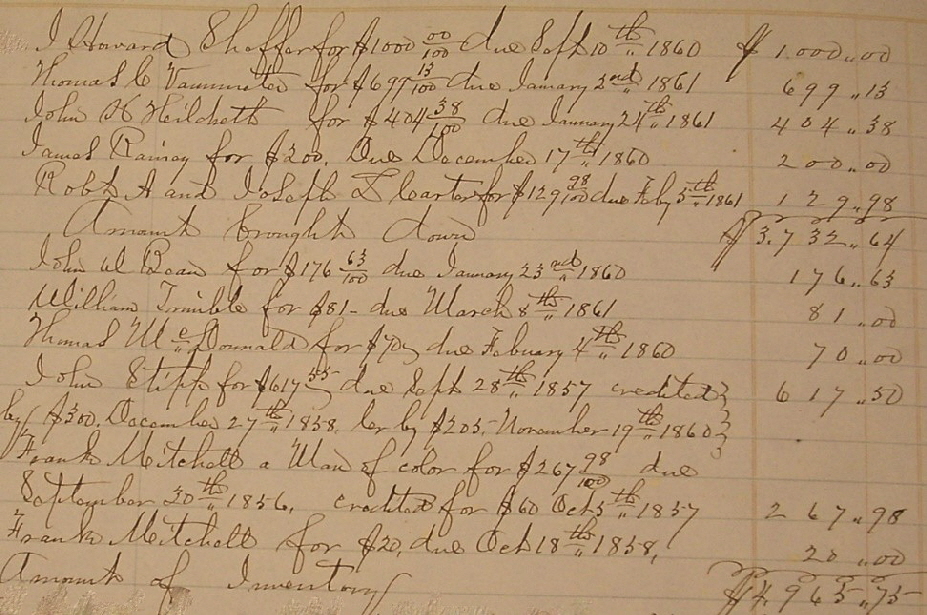

The most valuable part of the estate, however, was notes that Moses held on a number of wealthy farmers.

- W. O. Thompson 1200.00

- J. Howard Shaffer 1000.00

- Thomas C. Vanmeter 699.13

- John K. Hildreth 404.38

- James Rainey 200.00

- Robert A. & Joseph L. Carter 129.98

- John W. Bean 176.63

- William Trimble 81.00

- Thomas McDonnald 70.00

- John Stipp 617.55

- Frank Mitchell (a man of color) 267.99

- Frank Mitchell 20.00

These IOUs totaled nearly $5,000, or the equivalent of $155,000 today. These were designated in the inventory as “cash notes” whose interpretation seems unmistakable: Moses Robinson had lent large sums of money to white men in the neighborhood. Equally significant is the fact that Moses’ executor, John Whitesides, diligently pursued each borrower and managed to collect essentially the full face amounts of the loans—with interest!

Some of the Notes in Moses’ Estate Inventory, 1861

While we have only a handful of estates of free blacks to compare to in Clark County, we can say that Moses’ was unique: it is the only one to include notes of any kind.

How Moses succeeded in accumulating such astounding amounts to lend is a mystery. With boots selling at retail for $2.75 at that time, he would had to have sold nearly two thousand pairs—and saved every penny.

Moses’ accomplishment would be all the more remarkable and a testament to his acumen if he accomplished this without knowing how to read and write. This is presumed from the fact that few enslaved persons were literate and that he signed his will by his mark. However, the fact that he owned two bibles and a hymn book suggests that he could read. He may have educated himself between the year he signed his will (1849) and the year he died (1861).

Moses’ will devised $550 apiece to Sarah Jane, Andrew, and Permelia, “it being the amount that I have already given to my daughter Emily.” This could have been the amount Moses spent to purchase her freedom.

The will then directed his executor to use the remainder of the money collected to purchase farmland for his children. In 1863 the executor, John Whitesides Jr., purchased two tracts of land at the northern end of Indian Old

Fields, on the headwaters of Upper Howard’s Creek. For a total of 107 acres, the estate paid John Duckworth $3,900, or $36 per acre.

The land was not the most desirable in the county, and the price was no bargain. The property stood on a poorly watered ridge and was well back off the county road. Farmland in Clark County at the time sold for a wide range of prices, from as little as $4 an acre for third-rate land to $70 an acre for prime farmland (Inner Bluegrass land in the Van Meter Road area). The higher prices per acre indicate well-developed properties with improvements such as houses, barns, cleared fields and fenced pastures. A cursory examination of deeds of that period found land on Upper Howard’s Creek selling for $11 and $24 per acre.

Land Purchased by Moses Robinson’s Executor from John Duckworth

A possible explanation for the price of the Robinsons’ land being higher than whites would have paid for the same could be that many landowners would not sell to blacks, and the few willing to do so demanded a significant premium. (It was not uncommon to find a clause forbidding “sale or rent to Negroes” in Clark County deeds up through the mid-1900s.)

The 107 acres was divided between Jane Wilson, Andrew Robinson and Permelia Alexander.

Land Purchased by Moses Robinson’s Executor from John Duckworth

A possible explanation for the price of the Robinsons’ land being higher than whites would have paid for the same could be that many landowners would not sell to blacks, and the few willing to do so demanded a significant premium. (It was not uncommon to find a clause forbidding “sale or rent to Negroes” in Clark County deeds up through the mid-1900s.)

The 107 acres was divided between Jane Wilson, Andrew Robinson and Permelia Alexander. Emily Mitchell had died by that time. This land became the nucleus for the settlement called Dry Ridge.

Children of Moses Robinson

Moses Robinson left a record naming his four children: Emily Mitchell, Jane Wilson, Andy Robinson and Permelia Alexander. Descendants of three of the children inherited the land purchased by Moses’ estate in 1863. Most of the land is still in the hands of these descendants.

Emily Robinson Mitchell (c1814-c1862)

Moses purchased his daughter Emily then had her emancipated along with her two children, Sarah and Dickerson, in 1841. The certificate described Emily as “colour black, about 5 feet eight inches high, aged about 27 years.” Sarah was “bright yellow, about three feet four inches high, aged about six years” and Dickerson was “aged about three months, colour yellow, healthy looking & common size.”

Emily married Frank Mitchell and they lived in Fayette County. They were listed as free blacks in the 1850 and 1860 censuses. Frank was a farmer and in 1860 owned real estate valued at $2,310 (equivalent of $72,000 today). Their children found in the census included Sally, Dick, Easter, Betsy, and Moses. Milly Robinson, age 65, resided with her daughter Emily in 1850. There is no further record of Milly; her death date is unknown.

Based on their census neighbors, it appears the Mitchell family lived in eastern Fayette County, north of US 60 near the Clark County line—only about 3 or so miles from Moses Robinson’s home in Clark County.

The executor of Moses’ estate reported in August 1863 that “Emily Mitchel has died since the death of Moses Robinson [1861] and her one part remaining in the hands of the Executor and now due her children amounts to the sum of $766.27.” There is no evidence that Emily’s children ever lived at Dry Ridge.

Jane Robinson Wilson (c1823-c1897)

Sarah Jane, usually called “Jane,” was listed along with an unnamed child in Thomas Ellis’ 1848 estate inventory. Ellis’ will called for them to be freed after his wife’s death. Moses’ will of 1849 gave her name as Sarah Jane and her husband’s as Charles, with no surname. His name was Charles Wilson; their marriage record has not been found.

After Moses’ executor purchased land in Indian Old Fields, Jane received her share, 34½ acres, when it was divided in 1872.

The census of 1870 shows Jane living on the land with her husband Charles, a farmer. Charles died in 1879. No record was found of Jane’s death, which occurred in late 1897 or early 1898.

Jane and Charles Wilson had seven children: Charity, Sally, Richard, Elizabeth, Mary, Robert, and Charles. A portion of the Dry Ridge land awarded to Jane is still held by her descendants.

Andy Robinson (1835-1904)

Andrew Robinson, usually called “Andy,” is first recorded along with his sister Jane in Thomas Ellis’ 1848 estate inventory. Ellis’ will called for them to be freed after his wife’s death. He was a free black living with his father in 1860, working as a day laborer, and owning personal property valued at $300. The tax list for that year shows he owned two horses valued at $100.

The deed for the purchase of Dry Ridge land by Moses’ executor was made in 1863. The tax lists for 1862 and 1863 show that Andy remained in the same district where he resided 1860, possibly still living in his father’s old house.

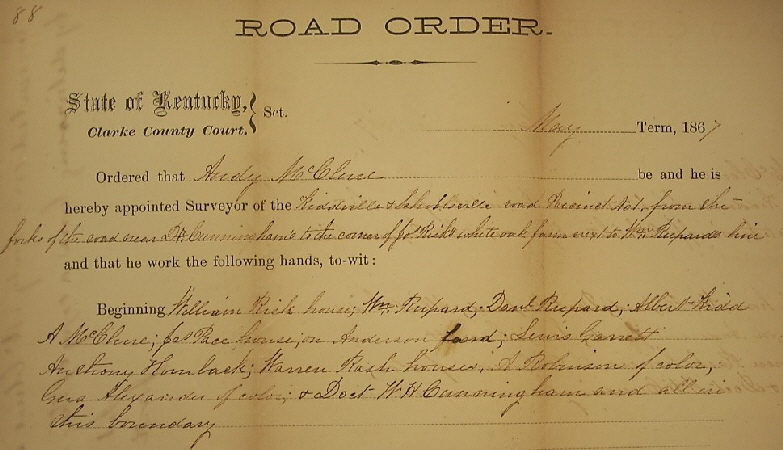

Andy, and perhaps his brother-in-law Gus Alexander, may have come out to live on the Dry Ridge property as early as 1864. The earliest record we can find for the Robinson family living in the area is 1867. That May, Andy Robinson and Gus Alexander (Permelia’s husband) were listed on a county road order. In the 19th century, local residents were expected to work on roads in their neighborhood. The court appointed Andy McClure supervisor of the Schollsville-Kiddville Road and named the hands required to work, which included “A. Robinson, of color” and his brother-in-law “Gus Alexander of color.”

In 1870, Alvin Duckworth was appointed supervisor of the road and Andy was again named as one of the hands. Gus, apparently having returned to Fayette County, was not listed.

1870 Road Order

Andy married Agnes Prewitt, who was ten years his junior. The 1870 census reveals that they were living at Dry Ridge. Although Andy did not receive a deed for his land until two years later, when the property was divided, the census records him with $1,440 of real estate. He also had $500 worth of personal property, which would have put him among the most prosperous blacks in Clark County at that time. That same census designated Andy as illiterate (cannot read or write) but that may not be strictly correct. We know that Andy purchased his father’s bibles and hymn book. And we wonder why he would do so if he could not read.

As an indication of the hard times experienced at the new settlement of Dry Ridge, in the 1870 census Andy listed his occupation as “farm laborer.” In other words, even though he owned his own farm, he must have had to work for wages in order to support himself and Agnes.

Andy’s wife Agnes died in 1875. A decade later we find he was married to “Cinda” who was five years his senior. Andy died of “dropsy,” or heart failure, on October 6, 1904. We have not learned more of Andy’s wives and no children have been identified.

On the tax roll of 1874, “Andrew Robinson” was listed in the Kiddville Precinct as the owner of 34 acres of land valued at $590 and horses valued at $60. He also reported harvesting 30 bushels of wheat and 100 bushels of corn for himself.

The 1874 tax list was completed in May. In November of that year Andy lost a judgment in the circuit court to Thomas M. Eginton for a debt of $200 plus interest accruing from April 1873. He had paid back $84.50, and the court ordered a portion of his property to be sold in order to pay the balance. Andy must have been able to pay off the debt before the property went to auction.

In the 1880 census, he gave his occupation as “farmer,” which may indicate he had become self-sufficient landowner, no longer having to work for wages. However, he would soon encounter more financial difficulties and had to borrow money, which ultimately resulted in losing his Dry Ridge land.

Winchester National Bank sued Andy for a debt of $150 in Clark Circuit Court in 1886. It possible he got the bank loan in order to pay off Eginton. Midway through the case James Flanagan replaced the bank as the plaintiff, presumably having purchased Andy’s note. The court ordered Andy to pay the loan back in three installments, and that is the end of the record in the order books.

In 1890 the court ordered the sheriff to sell his property at auction. Andy’s neighbor, A. F. Duckworth, was the high bidder for the land at $200. He did not pay immediately but gave his bond for the purchase price. Four years later Richard Ware put up the money, and Duckworth directed that the deed should be made out

to Ware. Fortunately, Andy did retain a life estate in the land, which permitted him to reside there until he died.

Andy’s land theoretically was worth about $1,300 in 1863 when it was purchased for Moses Robinson’s three children ($3,900 ÷ 3). In other words, A. F. Duckworth paid $200 for the land his brother John sold for $1,300. This appears to reflect the asymmetry between white sales to blacks and black sales to whites.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

The earliest document listing the black community here as Dry Ridge is found in Andy’s death record in 1904. The entry actually states that his birthplace was Dry Ridge. We know he wasn’t born there, but associating his name with the place name gives us confidence to identify it as the community where he lived.

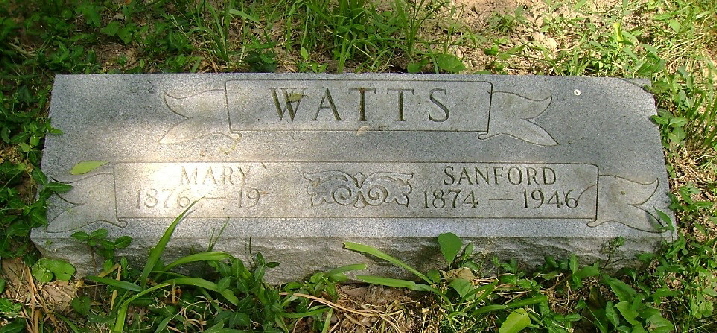

Dry Ridge shows up in numerous death certificates as a “place of burial.” For two of these—Sanford and Mary Watts—their death certificates stated they were buried at Dry Ridge and their names also appear on gravestones in a small cemetery on Andy’s tract of land.

The cemetery also has a stone for Henry Quisenberry, whose death certificates states he was buried in the Andy Robinson Graveyard.

Mary and Sanford Watts Gravestone in the Cemetery on Andy Robinson’s Farm

Permelia Robinson Alexander (c1830-bef. 1870)

Permelia was the third child of Moses Robinson owned by Thomas Ellis, along with her daughter Emily. Thomas left directions in his will for his slaves to be freed at his wife’s death. She died in 1858.

In the 1860 census, before Emancipation, Permelia and her husband Gus Alexander were recorded with their family as free blacks in Fayette County. They lived very near Permelia’s sister, Emily Mitchell. The couple had seven known children: Emily, Amanda, Moses, Laura, Florence, Andrew and Minnie.

We do have a record of Gus residing at Dry Ridge in 1867, when he and Andy Robinson were called to work on the Schollsville Road. It seems likely that Gus would have had his family there with him.

Permelia had died before the next census was taken. In 1870, Gus was living in Fayette but with a new wife, Ailsey. Of Emily’s children, only Moses was still living at home.

In 1871 Gus brought suit to have the farms divided among Moses’ children. In 1872 a deed was issued to the “heirs of Permelia Alexander” for her share of the land purchased out of her father’s estate. Her son Moses, called “Mose,” came to Clark County and lived on her land.

Mose and his children eventually bought out the other heirs. The records do not show that any of Permelia’s other children ever lived at Dry Ridge.

Community of Dry Ridge, 1870-1940

According to Clark County tax rolls, the first arrivals at the new settlement at Dry Ridge were Andy Robinson and Gus Alexander, who were definitely there by 1867. Whether they had their families with them that year is not known. For 1870 and beyond we have census data to rely on.

There are no documents listing the names of people who lived at Dry Ridge through the years. As a way around this obstacle, we report here our best “guesstimate” of the residents over time. U.S. censuses for the years 1870 through 1940 have the names of all residents in Kiddville Precinct, where Dry Ridge is located, and the race of each—designated as white, black or mulatto. These results are summarized below.

Year Houses Total Residents

1870 4 23

1880 11 68

1900 8 40

1910 10 38

1920 10 35

1930 7 39

1940 7 32

From its early beginnings (4 houses, 23 residents in 1870), the community grew over the next decade to 11 houses, 68 residents, before reaching more stable numbers from 1900 through 1940. Due to the imprecision of the methodology, however, these estimates probably reflect the number of persons living in the Dry Ridge area rather than living specifically on one of the three ridge farms of Moses Robinson’s legacy.

This analysis also identified the families living on Dry Ridge (or the Dry Ridge area). The more detailed chart below lists the census year, the head of the house, and number of residents in the house.

1870 Charles Wilson 7

Israel Lewis 6 4 Houses

Henry Quisenberry 8 23 Residents

Andy Robinson 2

1880 Samuel Hines 10

Harry Haggard 7

Jordan Calmes 6

Mose Alexander 2

Richard Wilson 6 11 Houses

srael Lewis 3 68 Residents

Henry Quisenberry 4

Alvin Chorn 3

Jane Wilson 13

Andy Robinson 2

Leaven Hines 9

1890 census records lost

1900 Israel Lewis 5

Harry Haggard 10

Mose Alexander 9

Andy Robinson 1 8 Houses

George Davis 5 40 Residents

John Watts 2

James Daniel 4

Henry Quisenberry 4

1910 Charley Johnson 7

George Cooper 4

George Davis 4

Homer Nelson 4

Israel McClure* 6 10 Houses

Sanford Watts 2 38 Residents

Mose Alexander 4

Henry Quisenberry 2

Henry Bowen 4

Alvin Chorn 1

* previously listed as Israel Lewis

1920 Samuel Cooper 2

Sanford Watts 2

McKinley Garrett 4

Alvin Chorn 2 10 Houses

Edward Davis 4 35 Residents

George Davis 2

Sam Strong 7

Stanley Alexander 2

Ike Beatty 4

Homer Nelson 6

1930 Carl Davis 7

George Watts 1

Amanda Alexander 4 7 Houses

Ike Beatty 11 39 Residents

Sanford Watts 2

Homer Nelson 5

Walter Davis 9

1940 Stanley Chenault 3

Carl Davis 10

Sarah Nelson 4 7 Houses

Ollie Alexander 4 32 Residents

Sanford Watts 2

Walter Davis 8

Katie Davis 1

The 1950 census will not be released until April 2022. We believe it was during the 1950s that the Dry Ridge farms began to be abandoned.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

Very few visible remains of habitation can be found on Dry Ridge today. The crude map below shows the approximate location of home sites with the evidence for each.

Remains of Possible Home Sites 1—Jane Wilson’s house, still standing; 2—old cistern; 3—a pair of foundations; 4—Andy Robinson home site; 5—old cistern; 6—remains of an old cabin or shed. Solid circles represent the Wilson Cemetery (top) and Robinson Cemetery (bottom).

We have only very few personal recollections of Dry Ridge. One of the last living residents of the community is Gretchen Nelson Hale, born in 1934. She recalls living on the ridge as a small girl.

My name is Gretchen Marie Nelson. I was born on Dry Ridge in 1934 and I’m now 86 years old. I was raised by my grandmother, Sarah Jane Watts. After her house burned down, we moved to Winchester in 1942.

There were about six families still living on Dry Ridge when we moved to Winchester (1942). Aunt Kate was still there. She lived there until she died (1954). Sanford Watts and several Davis families were still at Dry Ridge when we left. I remember Cousin Carl [Davis] and Cousin Walter [Davis].

I remember my Aunt Kate. She was thin, played the piano. Her brother, Pete Watts, played the fiddle. She married George Davis. You could see her house through the trees from our house. We could also see Sanford Watts’ house to the south.

There was a schoolhouse on Dry Ridge. My grandfather, Homer Nelson, was principal or superintendent of the school at one time. I do not remember hearing of a church. They all went to the Methodist church at L&E Junction.

There were three cemeteries. One is where my family is buried (Wilson Cemetery). The second is where Sanford Watts is buried (Robinson Cemetery). The school was close to this cemetery. The third cemetery was farther south of those two. It must have been for the Alexander or Beatty family.

I started to school at Indian Fields. Had to walk out our road to Schollsville Road then ride the bus to school. Sometimes my grandmother would walk out with me. My teacher at Indian Fields was my aunt, Eleanor Fletcher. After Indian Fields School closed, she taught at Oliver Street School before integration. She lived at West Bend, a little black community in Powell County.

Ernest Pasley, whose family lived in the neighborhood, also shared some of his memories about Dry Ridge.

There were a number of homes. My father accounts digging graves for the family at the Wilson Graveyard in the corner of this tract. He says they had homes built on the left and right of the old road through the middle of the 35 acre (Wilson) tract. The church and old schoolhouse had porches like an old city town per my dad. One of the Davis family was a pastor and eventually moved the congregation to

the church on L&E Junction Road. As a boy there were two old homes falling in. There was, or is still, the original old Wilson homestead standing.

Andy Robinson and his wife had at least two children who died very young and are buried on what was his 35 acres. Him, his wife, children, and some of the Alexanders are buried with the survey markers from the railroad as tombstones. In my lifetime you could never see any of his home. My grandfather always said the graveyard was in the corner of the yard.

Ernest has an old Remington rifle that he said Andy gave his grandfather.

⁎ ⁎ ⁎

The somewhat stable population of Dry Ridge from 1910 to 1940 masks an important trend that was occurring: people were leaving the ridge during this period. When children of the families that settled Dry Ridge began to have children of their own, the number of individuals rose exponentially. The fact that this increase is not observed in the Dry Ridge population means that many of the offspring were moving off the ridge. There were two main causes of this out-migration.

First, due to its small land area and limited resources, Dry Ridge simply could not provide livelihoods for a larger population. Many children and grandchildren of the pioneer families were forced to move away in order to find means of support. The first to leave did not go far. We see them showing up in Winchester, Lexington, Paris, Georgetown, Mt. Sterling and other nearby towns.

The second major factor affecting out-migration was the Great Depression that began in 1929 and continued until the Second World War. During this period we see people moving farther away from home chasing after ever more scarce jobs. The trend for Dry Ridge mirrors that of other poor regions of the state (e.g., the mountain counties of East Kentucky), that is, residents leaving the state to find work, principally in the more industrialized North. During the Depression, Dry Ridge family members began to show up in Cincinnati, Dayton, Detroit, and Indianapolis.

This trend became obvious when examining census data tracking Robinson family descendants. Examination of the obituaries in the following chapter will show numerous examples of the phenomena.

After World War II, as Kentucky’s small farms began disappearing, crossroad communities in Clark County began drying up. Ford, Ruckerville, Becknerville, and Vienna fell victim to the relentless spread of urbanization. More importantly for Dry Ridge, the neighboring communities of Schollsville and Kiddville also vanished.

We find Dry Ridge suffered the same fate as Clark County’s other rural black communities—Lisletown and Hootentown. Thus, in the 1950s Moses Robinson’s last descendants on the ridge left to find the “good life” somewhere else.

Afterword

Dry Ridge is a ghost town today. But it deserves to be remembered and preserved as the legacy of Moses Robinson, the gift of land he left to his children in 1861. Three of those children settled the land and a community of sorts persisted there for nearly a century.

In 2018, the Friends of Dry Ridge, Inc. was established as a 501(c)3 non-profit organization committed to preserving the memory of Moses Robinson and the history of Dry Ridge.

Several projects have already been accomplished by volunteers. The home sites have been identified, two cemeteries have been cleared and are being maintained, and the perimeter of the properties has been fenced. The present work is an effort to document the history of the Robinson family and the community of Dry Ridge.

**************************

The Story of Dry Ridge is the work of Harry G. Enoch, Bobbi Newell, Lyndon Comstock and Tom Rich

WINCHESTER BLACK HISTORY

AND HERITAGE COMMITTEE

© 2019-2024, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED,

Winchester Black History and Heritage Committee

Website Designed and managed by Graphic Enterprises